On pizza and being missed

There's nostalgia and there's missing. Pizza, hopefully, lives in the latter category. One San Francisco parlor nears earning that place in my heart.

We are allowed a few basic proclivities in this life, aren’t we? Can’t we dip into the likely ubiquitous for moments of rapture? If we can bask in that place, I’ll tell you: I had a mid-August basic moment at Dolores Park.

My friend Antony joined my wife, Lucie, and I for a late afternoon viewing of the sun boxing out the fog long enough to paint the skyline in light. From the corner, Gay Beach as it’s been called, the light bounces off Salesforce Tower like that kaleidoscopic rhombus when Team Rocket blasts off again. We rocked up, sat down, and unfolded two cardboard boxes weighed with artisan pies, ramekins of magical buttery cheesy stuff. We ate pizza.

Pizza’s been knocking on my door. It’s been coming to mind out of the blue. I sit down to write something “important,” something about coffee’s shocking surge in commodity prices, about how it’s never been a better time to go vegan with H5N1 hitting California’s dairy farms. It doesn’t matter: pizza rolls right over any lofty intention, lingering over my dome like one of those cloudy thought bubbles in the Peanuts.

Maybe it’s because pizza has something to tell me. Dwells somewhere in these arenas, like Gladiator II if it had something to say. If anything, I tell myself it’s good to move the fixation top of mind topic straight across the desk to the outbox. It’s only done by donning gloves and getting into the weeds, though they’re springing up seemingly from nowhere. I’m pretty sure Hanif Abdurraqib described these fascinations and this exploratory work as emotional investigation at a City Arts and Lectures talk in April. He’d k now; His piece on risotto as a way to cope with the world hit different.

So let’s apply that high-mindedness to pizza and being missed.

I only just embarked on this pizza campaign in the summer. I’ve eaten a lot of gluten-free pizza in my life. Most of it sucked. My Grandma Floy would make these hulking pizzas in the experimental mid-Aughts, shellacked in ground beef and whole blocks of non-descript cheese. They were close to casseroles and kind of ruled. If a pizza wasn’t better than that, I wasn’t going to pay $2 more than its wheat-ful pizza counterpart.

It might’ve been Flour + Water Pizzeria’s gluten-free pie that got the wheels turning. I was enchanted by the time and thoughtfulness that went into the pizza; That intention absolutely showed through in each oily, chewy bite. It might’ve been Mr. Singh’s Curry Pizza for bringing Indian pizza into my life at long last. But, to be honest with you, that afternoon in Dolores Park I was eating pizza from a new lover. The Tenderloin’s Outta Sight.

It was a moment I can only imagine compares to Ceasar crossing the Rubicon and, over the water and after all that work, pizza stretches into the distance, fields and fields of at last at last at last.

The difference between nostalgia and missing walks the same razor’s edge Somerset Maugham wrote about in 1944. Squint hard enough and they can get confused, twins on the first day of school. The Eldians in Attack on Titan know the difference between reminiscing and longing.

There’s a lot to write about regarding Attack. I’m wrapping the show for the first time (about a decade late, I realize) and much of its take-aways apply to nationalism. It’s not subtle, and it’s more relevant than ever. But for our purposes we’ll focus on two lesser-known characters: Falco and Gabi. These two kids are trying to get back to their home country Marley, to their families trapped in a World War II-era ghetto.

In the fourth season, they’re caught on an island full of people they were raised to consider devils. They were radicalized to kill any of these islanders on-sight. Now they just want to get home. Not to a memory, but to the community that reared them, a desperate place they still call home. They’re eager to return, but it can’t be rushed. “We can’t do anything on an empty stomach,” one of the islanders tells the young would-be warriors.

The missing of people and place is universal, whether one’s lived through a cannibalistic anime regime or not. Falco and Gabi learn in short order that, beyond all their righteousness, leaving Marley has them missing their families, their friends. On a much chiller scale, comic and love of my life Caleb Hearon says on his podcast So True “let us miss you.” It’s his response to the temptation to overdo social media, to flood the Internet with posts and content and Takes. My dad details something similar when describing charisma. “There’s power in pausing,” he used to say. “Charisma is in making people wait.”

Pizza may have that power over me due to my own waiting. I was diagnosed with celiac disease at ten. I was rail-thin, couldn’t articulate the throbbing pains my tiny body suffered until adolesence. I called them “pangs” since the bee-sting like pain felt like a description I had to save for when it was particularly bad.

Like Tantalus before me, pizza was always nearby and out of reach. No precious allergen-sensitive childhood was mine: My brothers and cousins were still rocking with normal-ass pizza all around me, a veritable gluten minefield. I didn’t care. I always watched Munchie’s Pizza Show, stayed up to date on whatever new flours might have come through the two grocery stores in my hometown.

I missed a food I’d never gotten to fully appreciate. In high school, when the first nascent signs of millenial foodie-ism crept into teenager brains, I flexed and told people Escape from New York Pizza was one of California’s finest. I knew because I visited San Francisco at 14 years old and my dad took us to the Haight Street shop. It didn’t matter I’d never tried the pizza. I knew it was cool, wrapped in neon with people standing all around, oil dripping to the paper plates below.

Someday I wouldn’t have to wait. Then I ate Outta Sight pizza.

That day arrived more and more as gluten-free flours and crusts became less gummy, less crispy, and more well-structured. Outta Sight’s crusts bring these progressions to bear in fantastic display. The crusts are springy, the flavors careful, portions generous. It’s not cheap — the day the costs balance for gluten-free pizza makers may still be on the horizon — but it doesn’t matter. Picking up the pies in a parlor with Bart Simpson sitting on a shelf and Mos Def’s iconic too-close visage painted on the wall behind the register, one is forced to sigh that old cliche: at long last, this must be the place.

Ellensburg’s Pizza Hut, the one across the street from the Jack in the Box and sharing the same blacktop as the Mexican place El Caporal II — inexplicably a sequel until much later when I learned of the first El Caporal in nearby Cle Elum — held a rare place in my heart. There was a buffet. One of the only in town. I’d shove my hands in my pockets to fish for change to drop into the vending machine, plastic toy animals and sticky hands to fling across the restaurant depositing like golden tickets. My heart lifted from my chest playing The Simpsons and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, teaming up with my cousins to whack those creepy white rabbit guys with Marge’s vaccuum. I couldn’t be sure life would get more fun.

But it was my second favorite pizza parlor in town. The gold medal went to Grant’s.

In my six-year-old mind Grant’s was a huge brick-walled viking hall of splendor and diversity. There was a party room, a main sitting area, a back seating area, *and* numerous rooms crammed with arcade games. If Pizza Hut was a close silver thanks to the nostalgia of The Simpsons and bottomless cheese pizza, Grant’s won out thanks to family, friends, and birthdays.

My mom worked there in the late 1970s when it was called Frazzini’s, surname to its original owner. My dad would bake these birthday cakes shaped like planes, trains, buses; Revealing that year’s creation at Grant’s was a present all in it’s own right. (Heather O’Neill gets at this tremendous joy in her piece “Cake Walk” for Serviette Magazine.) Like my hometown’s annual rodeo or the blitzing hot August days rope-swinging into Carey Lake, Grant’s was always there, nestled between a seemingly ageless photocopy shop and, eventually, a fro-yo shop.

Eating the thin crust pizza there by the busload was a part of a life when everything was on the menu. The time of life when collecting 150 Pokémon cards to show my friends at school was not just bonding but a sign of discipline, like we, too, could take down the Elite Four. The time of life when I’d wait outside on mom’s porch for my dad to pull up in his forest green pick-up truck Sunday evenings as the sun set over Water Street, when indulging my body that puzzled the doctor with ribs splayed like an opening flower was, somehow, medicinal. Eating at Grant’s was one of life’s rare good highs, uncomplicated bliss.

These pizza places, Outta Sight or Grant’s alike, become more than nostalgia. It’s not nostalgia to write a love letter. If it is, meaning this feeling is just the syrupy gaze of wishing, then it’s perhaps a co-dependent relationship, as Frank Ocean would call the bad religion of an unrequited love. I’m talking about the architecture of a person, place, or thing that lives on inside us and manifests as a part of our life. It’s largeness becomes part of who we are in more than a memory, more than fantasizing about the past.

Abdurraqib nails this tension in his newest book There’s Always This Year. His hometown of Columbus, Ohio, too, is a complicated place. To him, desperate (maybe not so desperate as Attack on Titan’s world) and filled to the brim with who he is and who he sees himself as. Coronating these spaces is, for some, all that really matters. “I want to make something of this place,” Abdurraqib told Shereen Marisol Meraji during that City Arts & Lectures talk.

Outta Sight isn’t that for me just yet. I think it’s been on my mind so much, though, because that afternoon with Antony and Lucie was one of my last in the Paris of the West for what has felt like a long, long time. Like Grant’s lives in the corners of my heart, brick-laid like my hometown, I realize now that San Francisco’s pizza parlors do, too. Like playing video games with my cousins, like a trip to a new city with my dad, the phenomenon of missing is a many-headed animal, born again and again.

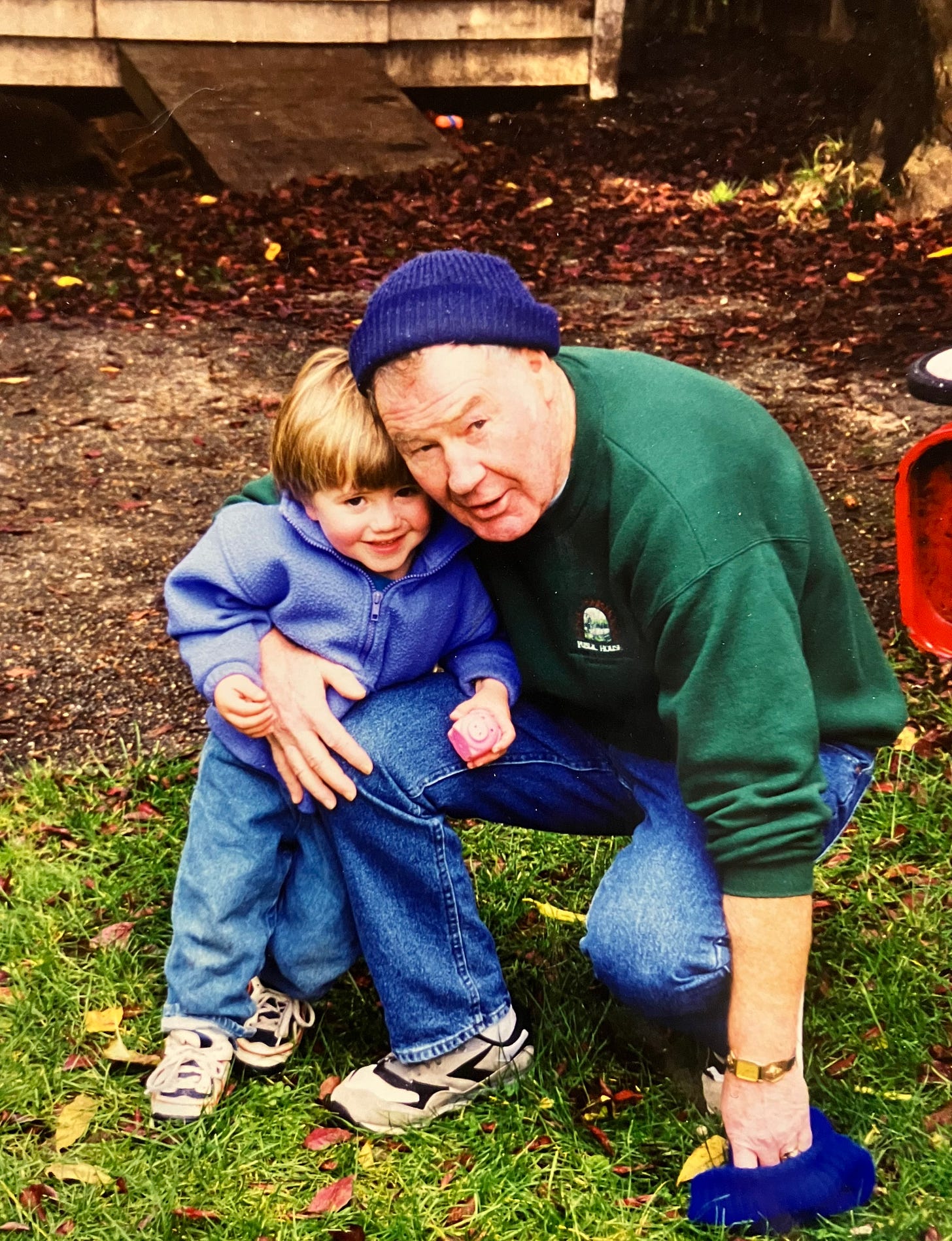

My grandfather died mere hours before the memorial service of my uncle a few weeks back. At this now double-memorial, I thought about my childhood and his infrequent visits. There is now one fewer person who loved me through a birthday at Grant’s on the face of this burning world.

I shouldn’t be surprised he died with dramatic timing. Here was a man who knew all about charisma. He knew how to make people wait, a thoughtful speaker.

Like him, I do want to be missed. Like a pizza place, I want to be pined after, to be top of mind, to be a hesitating text message re-written and maybe never sent. To be worth crossing nations for a taste. To be the oven laid in another heart.

Oh, wow, Paolo. Thank you for your gorgeous writing and you gorgeous thoughts.