On Irish butter and an American wake

Isolationism is appealing in troubling times. But from an island's dairy industry to the most infamous sunk ship of the modern era, we already know it's a bad idea.

There’s a stoney corner in Cork with smart orange-red doors dedicated solely to the creamy majesty of Irish butter. It’s called the Butter Museum and as soon as one walks in they know they’ve arrived in a special place. The small-ish building’s first floor is dedicated to ancient butter-making techniques and tools, the second floor to timelines outlining the product’s journey around the world from the island. The only staff on the floor turn a video on for guests when they arrive; Attendees sit in rapt attention as various officials from throughout Ireland wax nostalgic on the journey Irish butter has made to become a multi-billion dollar export.

I’m thinking a lot about the Butter Museum, export commodities, and national economies as I think about the recent American presidential election.

It’s worth saying now: This is not a “let that sunshine in” article nor a “so we fight harder than ever” rah rah situation. These just happen to be the strains that wove in my weird head when I sat with the news over the course of the first few days. What are actual economic and international plans Trump considers useful, and how might they actually play out? In the Age of the Take, it can be hard for me to remember that, while influencers and podcasters I enjoy may have lots to say about the national election, I’m probably better served by looking toward history and data rather than vibes alone.

And where better to learn these lessons than in Ireland’s butter museum.

The Butter Museum is more than a quirky food fascination. It’s a thrilling dive into how one commodity can vault a country from economic dependency to elbowing out space on the Gini index. According to the museum, butter in Ireland was first made three-and-a-half thousand years ago. It went from a cottage micro business dotted throughout the pastoral countryside, which didn’t even have electricity until 1950, to a now billions per year export market.

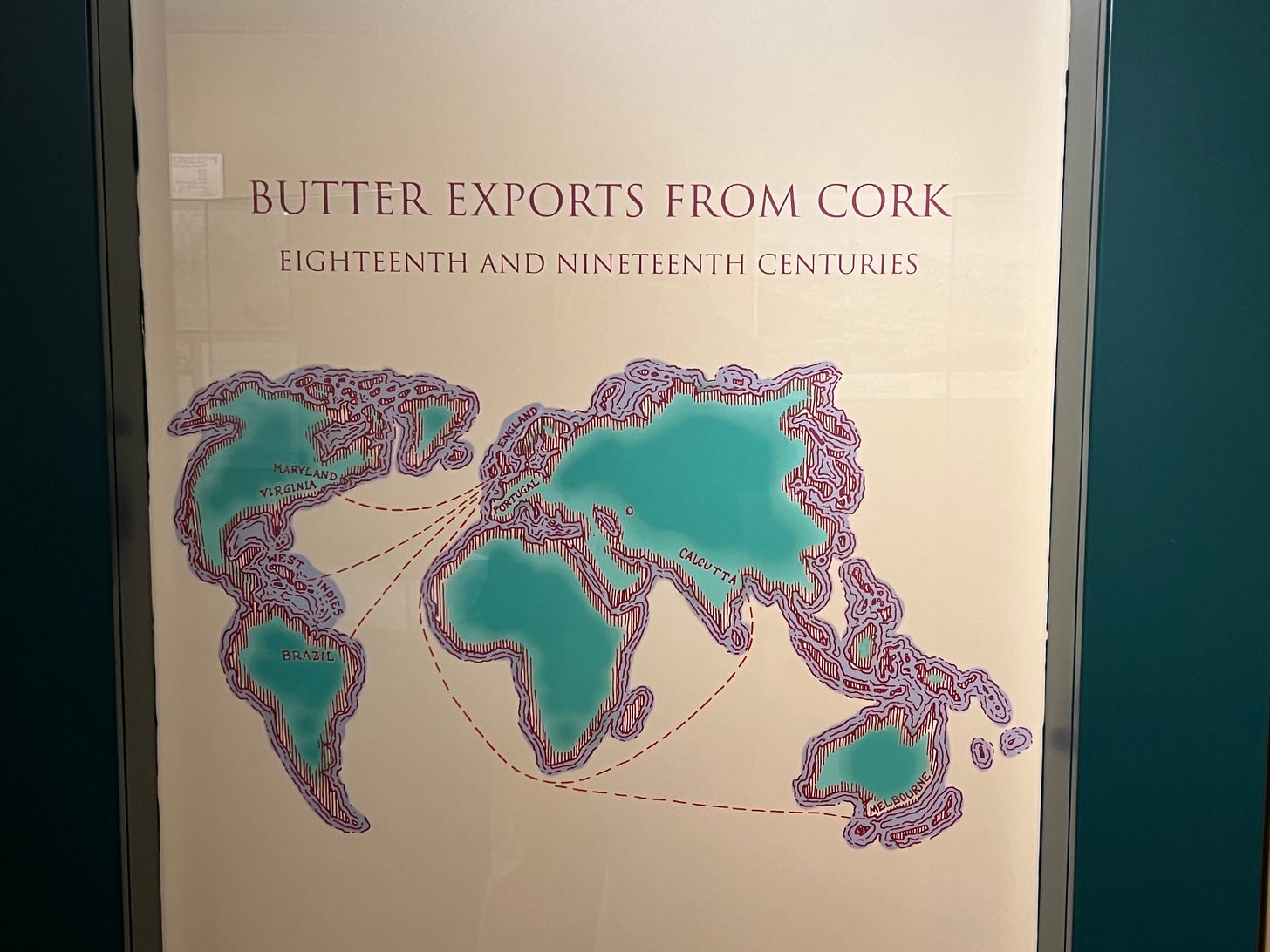

An important part of the butter market’s growth is understanding its inception as a product ballooned by and for the British Empire. Before that energy coursed through the country it was mass-produced for the invading force. The British lasered in on Cork’s harbor, the world’s second-largest behind Sydney, Australia. That made it the premiere place for the United Kingdom to ship out all their food stuffs: coffee, sausages, and much more than just butter. These goods catapulted across the globe to keep the empire’s standing armies and colonial bureaucrats alike fed and strong.

That’s why butter became a source of Irish revolutionary pride in the early 20th century. People were tired of making this wonderful stuff for their oppressors, started plastering “Buy Irish Free State Butter” all over the place. In 1922 the Irish Revolution saw those supplies cut off; no longer was the dairy bound for navies and officers but for members of the nascent Republican Army. County Cork, where all that butter was being exported, is the home of Irish patriot Michael Collins and loads of other heroes in that movement. County Cork is known as the Rebel County, after all.

By 1962 the cooperatives throughout Ireland were churning out tons of the stuff, and the quality of the goods had long been understood by those lucky enough to eat it. Irish cows eat plenty of grass rather than the factory farmed crap we feed our animals in the United States; a former dean of the business school says in a video at the museum four-fifths of cows worldwide are indoors, but cows in Éire spend their lives almost entirely outdoors. This lifestyle turns the butter they produce a characteristic orange.

Kerrygold was launched by the National Dairy Association, advertising the kitchen-bound gold by “origin” like one might coffee or wine. TV commercials ran in those early days showing the butter aged to the sound of gentle harps. The spread-out cooperative structure consolidated into six large cooperatives in the 20th century, and the amount of foreign markets the butter was placed in thundered. Now Kerrygold is number two in the United States, and China is the second largest-export market for Ireland as a country.

A deeper dive is warranted to examine the cooperative structure that saw some 191 creameries by 1900, led by Anglo-Irish reformer Horace Plunkett. That research could determine if the consolidation by the National Dairy Assocation has broadly been a positive thing; It’s worth keeping in mind the Butter Museum is underwritten by the government and the NDA. For the purposes of this essay, I gathered my information from the museum.

Still, these efforts of government growth to underpin anti-imperial economic growth — trading with the world’s buyers and sellers on equal footing — are inspiring. Relying on the foundational principle of comparative advantage (an ultra-basic summary of which might be the idea that one country produces and sells things it it is good at producing and selling so another country can exchange their own goods for that thing) Ireland became financially independent.

We know Trump’s plans are more or less steeped in a diametric approach. Railing against foreign trade, the plan boasted through his campaign involves kicking out all of the workers who produce the scant goods the U.S. makes at this point and closing off the country from the international community. (See his brilliant behavior regarding the World Health Organization and various climate-centric groups in his first term.) His idea to imposing heavy tarrifs on foreign-made goods doesn’t square with what the United States imports (just about everything) and exports (intelligence services plus weapons).

And in regards to food, his strategy doesn’t add up. Not that anyone should need this data in 2024, but most recently in Transfarmation author Leah Garcés surveys the sorry state of our despicable beef, pig, and chicken industries. Of course, outside of small-holding farmers entrapped to meat tycoons, the majority of farm work in the country is done by Central and South American migrants. Mass deporting these workers, many of whom take jobs through legal means, and anyone associated with immigrants means what little the United States does make in regards to commodities (think some food stuffs like corn and soy, seasonal produce) will tremendously shrink.

There’s another must-visit cultural learning center in County Cork. The Titanic Experience was established in the the tiny town of Cobh since it’s the last place the Titanic ever docked. The modest port where Irish emigres left from the country in the 20th century is also located in Cobh. That stoic place, where Annie Moore pioneered a trail of migration, is fittingly called Heartbreak Pier. It’s weather-worn now, a sullen Tetris piece straggling into the Celtic Sea. One group of 14 that left on the Titanic from Heartbreak Pier came from Addergoole, a little town of less than 100 in County Mayo.

According to our chipper young guide, the friends and family that came to see off those 14 didn’t cry at their departure. One has to think the tears came just four days later when the ship sank under a rushed corporate hubris. No, the community that journeyed south to see them off held what was called an “American wake.” That meant a farewell full of singing, drinking, and dancing, sending their friends to a country that was simply too far away, too expensive to return from.

Visiting the Titanic Experience on November 9, I thought about the American wake I am watching in my home country. It’s not one of singing and dancing, rather it’s a collective mourning for all the rage-addicted folks across the political spectrum. There seems to be no winning in the States’s electoral politics, instead millions of people hoping their country could evolve into something it unlikely ever will be or praying for a country to be great again.

The similarities struck me again and again. Take White Star shipping line owner Joseph Bruce Ismay. He knew of fires aboard the ship as early as Belfast, where the ship was built, and kept on making poor choices like encouraging the boat to run hard despite hitting an actual fucking iceberg. Instead of putting his family on the lifeboats, he made sure to hop the line and save himself. That reminded me a lot of Elon Musk, sporting a “Colonize Mars” hat as the grandmother of his children takes to the Internet to beg for their passports. These starchy plutarchs are the same through history, watching the waters rise and beating the drum of growth no matter the cost.

Following the international path Trump and his bedfellows in the Heritage Foundation and AIPAC tout doesn’t lead toward economic stimulation, to put it weakly. To put it strongly might be to say that flying in the face of the basic tenants of national well-being by ignoring conventional humanitarianism and trade will sink an already flagging ship. But, yes, these guys, “elite” as a recent influencer called them on my Instagram feed, will for sure get richer. The Dow Jones went Icarus one day after the election. And according to Forbes Musk, Zuckerberg, and Bezos all personally raked in millions in the wake of steering into our uniquely American iceberg.

The Irish have made huge gains through the 850 years the nation has seen occupation from another ghost ship, the British Empire. Political economy sometimes develops this way, if a country is lucky. The decisions made by non-corrupt governments to strengthen a people through trade move it from colonized to decolonial. The millions of Irish who left the country for American shores couldn’t have known how Ireland would reject its overlords and build itself up. Instead they held wakes for each other, praying for better lives for their countryfolk overseas.

I, too, am celebrating an American wake. The well-intentioned online discourse — the “hang in there"s and the "let this be the wake up call”s — are processing techniques, off-gassing. But the reality is that whatever skills one has cultivated for their political praxis should be as well-tuned on November 3 as they are on November 4 as they are on November 5. Governments might save you, might build up a strong export economy, and might rally people together. Like during Ireland’s early 20th century revolution, though, that mostly starts by the people taking shit into their own hands.

Walking out of the museum, one can hear a video playing in the first room. It’s of an an Irish butter maker named Joan Collins, interviewed in her thatched roof home in the mid-1900s. Her voice creaks on a video that plays on the museum’s first floor. “Making butter is chancey work,” Collins says, “because it depends on the season.”

What a good read. I learned a ton. Thank you!